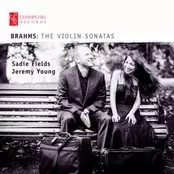

Brahms: The Violin Sonatas

CHRCD097

- About

Artist(s):

Robert Schumann wrote of Brahms in a piece in New Paths' 'Even outwardly he bore the marks announcing to us: 'This is a chosen one'....' Johannes Brahms' 3 violin sonatas are right at the heart of the violin repertoire. This disc includes all 3 sonatas, as well as the early work, Brahms's contribution to the FAE compositions suggested by Robert Schumann, the notes taken from Brahms's confidant and fine virtuoso violinist Joseph Joachim's motto frei aber einsam ('free but lonely')

Canadian/British violinist Sadie Fields enjoys a diverse career as soloist, chamber musician, and researcher. Since making her concerto debut at age fourteen, Sadie has performed across North America, the UK, and continental Europe, and further afield in Israel, New Zealand, and China. Sadie has broadcast on BBC Radio3, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, Radio New Zealand, NDR (Germany), and Swedish radio.

London born pianist Jeremy Young has gained a reputation as one of the UK's most respected and versatile musicians. A founder member of the Manchester Piano Trio, Jeremy has also partnered many of the worlds most distinguished musicians including Olivier Charlier, Mark Padmore, Julian Bliss, Liwei Qin, Thomas Riebl and Karine Georgian. He is currently the Head of Chamber Music at the RNCM.

- Sleeve Notes

Joseph Joachim's remarkable performances as a child prodigy made a lasting impression on his early audiences. Robert Schumann was among those who came to admire the young Hungarian violinist's penetrating musicianship and refined technique. It took no time for Joachim's prodigious talents to attract international attention and guarantee his place among the greatest performers of the age. In the autumn of 1853 Schumann, now based in D'sseldorf, invited the violinist to give the first performance of his Fantasy in C for violin and orchestra. The welcoming party included Schumann's composition pupil Albert Dietrich and a young pianist-composer from Hamburg, Johannes Brahms, who had recently been introduced to the Schumann family by their mutual friend Joachim. Schumann had earlier suggested to his young companions that they should jointly compose a sonata as a gift to Joachim. Each movement was to include themes based on more or less direct references to the notes F-A-E, a musical cipher for the violinist's motto, frei aber einsam ('free but lonely'). Brahms created the work's third movement, an ebullient scherzo charged with high rhythmic energy even in its most lyrical passages. The twenty-year-old fashioned abundant tricks and turns, not least in the movement's closing pages, to show Joachim's virtuosity to advantage. Dietrich later recalled that Brahms 'wrote the scherzo on a theme from my first movement. After having played the sonata with Clara Schumann, Joachim immediately recognised the author of each part.'

Brahms's portfolio of apprentice works included a string quartet and violin sonata, which he later destroyed, and two piano sonatas. The Schumanns were astonished by the striking maturity of the young man's music. Shortly before they collaborated on the F-A-E project, Robert wrote an article entitled 'Neue Bahnen' ('New Paths') for the Neue Zeitschrift f'r Musik in which he praised Brahms as a musician 'called to give expression to his times in ideal fashion'. It was as if, Schumann continued, the almost unknown talent from Hamburg had sprung 'like Minerva fully armed from the head [of the son] of Kronos'. Brahms was the real deal, shy and sensitive by nature yet, at this stage, self-assured when it came to composition. 'A well-known and honoured master [Joachim] recently recommended me to him,' wrote Schumann in his 'New Paths' piece. 'Even outwardly he bore the marks announcing to us: 'This is a chosen one'....' A more generous endorsement would be difficult to imagine. It led to the first publications of Brahms's works and attracted the attention of performers; it also set high expectations that fuelled the composer's determination to reinforce his technical skills through detailed study of counterpoint, variation and chorale harmonisation. Brahms later reflected with humility on his exceptional craftsmanship and expressed resentment at the struggle it had taken the boy from humble origins to achieve. 'It is not easy to find someone who has had as tough a time of it as I have,' he told Gustav Jenner, his only formal composition student.

Following Schumann's suicide attempt in early 1854, Joseph Joachim became Brahms's confidante in matters of compositional discipline and a constructive critic of his latest works; Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert, among others from the past, supplied the ideal examples on which he modelled his chamber music. The marriage of craft and invention present in Brahms's mature violin sonatas proved irresistible to professional and gifted amateur performers alike, adding to the significant flow of royalty income generated by sales of his music. Above all, the playing and listening public's attention was attracted and held by the lyricism that flows so freely through each work.

The Violin Sonata in G major Op.78 was written in P'rtschach, a favourite summer resort on the shores of the W'rthersee in Carinthia. Brahms had worked on his Second Symphony there in the summer of 1877 and returned the following year in retreat from Vienna's noise and bustle. He began work on his new violin sonata soon after arriving in P'rtschach and set it aside until his next visit at the end of May 1879. It is as if the surroundings helped the composer defeat those inner doubts that had led him to destroy at least three earlier attempts to create a sonata for violin and piano. There is no sense of conflict or striving in the music of Op.78; indeed Brahms cultivates a harmonious blend of the violin's tender, song-like sweetness and the piano's textural richness, bound together by their shared exploration of fruitful melodic and rhythmic motifs. The waltz rhythm of the opening theme, echoed throughout the first movement and heard again in the sonata's finale, calls out to be felt in the body, its forward momentum and fleeting pauses for breath complementing the principal melody's sensuous nature.

Brahms recalls his main theme as a brief taster of the movement's development section, transferring its melody to piano and enlisting the violin to play a simple pizzicato accompaniment. The melody's expressive potential is further examined in the development proper, buttressing the movement's thematic and structural integration. Rather than overturn the development with an abrupt recapitulation, Brahms takes time to recall what has gone before: he presents two gentle reminders of the opening theme in the violin part before restating it in full.

The thematic coherence of the Second Violin Sonata operates not just within individual movements but across the whole piece. Brahms based the work's rondo finale on material from two of his Op.59 songs of 1873, settings of Klaus Groth's 'Regenlied' ('Rain Song') and 'Nachklang' ('Reminiscence'). The composer provided clues to their presence in a letter to his friend, the surgeon and accomplished amateur musician Theodor Billroth. The finale, he noted was 'not worth playing through more than once, and you would require a nice, soft, rainy evening to give the proper mood'. Billroth recognised the reference in his reply: 'You rascal! ... To me the whole sonata is like an echo of the ['Regenlied']'. One plausible theory proposes that the pessimistic tone of Groth's poems, with their yearning reflections on lost youth, provided Brahms with an autobiographical programme and literary framework for his work.

The piece moves from G major in its first movement to G minor for much of its finale, while the work's central Adagio, cast in A B A B A form, includes a funeral march in E- flat minor. The recollection of the slow movement's main theme in the sonata's finale appears to have been influenced by a similar device (and theme) in Schumann's Violin Concerto, a late work withheld from publication by the composer's widow in consultation with Joachim and Brahms. In February 1854 Schumann experienced a waking dream in which Beethoven and Schubert appeared to dictate the theme of the concerto's slow movement, which he subsequently notated. It seems likely that Brahms had Schumann in mind when creating the Adagio of his G major Violin Sonata, a possibility supported by the evidence of a recently discovered letter of February 1879 from Brahms to Clara about her terminally ill son, Felix. 'If you play what is on the reverse side quite slowly, it will tell you, perhaps more clearly than I could myself, how sincerely I think of you and Felix.' Brahms included a sketch of an early version of his sonata's Adagio, identical in key and rhythm and similar in mood to Schumann's so-called 'last musical idea'.

Brahms's Second Violin Sonata, like its predecessor, was created in a rural setting. The composer spent the summer of 1886 in the Swiss village of Hofstetten, now part of the municipality of Thun, in modest riverside rooms rented from a local grocer. Here he completed his Op.100 and also sketched his Second Cello Sonata Op.99 and Third Violin Sonata Op.108. Elisabeth von Herzogenberg, Brahms's friend and former piano pupil, caught the work's mood in her concise description; it was, she wrote, 'constructed in the plainest possible way from ideas at once striking and simple, fresh and young in their emotional qualities, ripe and wise in their incredible compactness'.

While the Third Violin Sonata is more complex in structure than its Op.100 sibling, it is no less lyrical. The work's opening theme, at first gentle, then more passionate, may reflect the composer's anticipation of a visit from the high-spirited contralto Hermine Spies, with whom he was infatuated. It flowers as a song without words before yielding to a second theme in which the piano quotes directly from 'Wie Melodien zieht es mir', the first of his Five Lieder of low voice and piano Op.105, written that summer for Spies. Shades of two other Op.105 songs ' 'Immer leiser wird mein Schlummer' and 'Auf dem Kirchhofe' ' and 'Komm bald' Op.97 No.6 have also been traced in the songful sonata's finale. Early commentators noticed the similarity of the first movement's opening theme to Walther's 'Prize Song' from Wagner's opera Die Meistersinger von N'rnberg, although the resemblance appears to be more a matter of accident than design. The theme supplies rich material for the movement's central development section, which flows seamlessly out of its exposition. Brahms, the master of thematic transformation, here modifies his first theme with ingenious changes to its rhythmic structure before recalling the lyricism (if not the melodic line) of the movement's second theme. The development concludes as abruptly as it began, replaced by a conventional recapitulation of the opening section.

Two characteristic moods alternate in the Andante tranquillo, in which a wistful theme is confronted by the music of a sprightly triple-time scherzo. The juxtaposition of slow and quick sections recalls the formal contrasts already explored by Brahms in the Quasi Minuetto of his String Quartet in A minor Op.51 No.2. The contrapuntal interplay between violin and piano in the movement's slow sections evokes the spirit if not the style of early sacred music, while the scherzo's nature is clearly rooted in the soul of folk music. Following the Andante's final return, the movement closes with a sudden and uplifting echo of the scherzo theme. Donald Francis Tovey, a close friend of Joachim's and lifelong admirer of Brahms, described the opening theme of the Second Violin Sonata's rondo finale as 'one of the great cantabiles for the fourth [G] string'. It certainly matches the lyricism and exceeds the formal ingenuity of the work's first movement. Here Brahms contrasts the gentle warmth of his rondo theme with episodes of great expressive intensity.

With four movements and a striking range of ideas in its outer movements, the Third Violin Sonata is bigger in size and scope than both its predecessors. Yet the economy of its thematic development reflects Brahms's ability to build large musical structures without sacrificing formal clarity and expressive coherence. The work, sketched by the shores of Lake Thun in 1886, appears not to have been completed until later. The composer first showed the finished piece to a group of close friends, Clara Schumann among them, in 1888 and oversaw its publication the following April. Brahms dedicated the score to the pianist and conductor Hans von B'low, a tireless champion of his music and loyal friend.

Dark emotions and stormy outbursts belong to the world of the D minor sonata's outer movements. The opening Allegro is launched by a soaring main theme in the violin, the intensity of which is only lightened momentarily by the appearance of a second theme delivered by the piano in F major. Brahms subjects the movement's thematic material to a compelling process of transformation in a development section, underpinned by a prolonged piano pedal A, the dominant of the movement's home key. The recapitulation is interrupted to make way for a second development: there is clearly more to be said before the movement's contrasting themes can be reconciled and set to rest. Peace slowly emerges in the coda, constructed like the first development section above a piano pedal, and finds its resolution in the major mode.

The sonata's middle movements stand as ideal models of concision and concentration. The Adagio takes up where its predecessor closed, opening with an expansive D-major melody that receives subtle variation over the movement's course. Brahms continues to uphold virtue of simplicity in the third movement, which remains light in nature despite a brief shift into more turbulent emotional waters at its centre.

Thematic variation, a hallmark of the first movement's development sections, is woven into the finale's fabric, a sonata rondo in which Brahms explores the contrasts of two main themes ' one impulsive, the other hymn-like in nature ' and transforms their characters as the movement unfolds. 'I marvelled at the way everything is interwoven, like fragrant tendrils,' Clara Schumann wrote to the composer after receiving his work. Brahms subverts expectations of Classical sonata form in his finale, not least by nudging the exposition from D minor to C major and from there to a third section in A minor. His carefully designed tonal scheme, mirrored in part in the recapitulation, allows Brahms to vary the character of his thematic material, enriching and deepening the musical argument as the movement drives to its emphatic conclusion.

Andrew Stewart

- Press Reviews

- Delivery & Returns

If you order an electronic download, your download will appear within your ‘My Account’ area when you log in to the Champs Hill Records website.

If you order a physical CD, this will be dispatched to you within 2-5 days by Royal Mail First Class delivery, free worldwide.

(We are happy to accept returns of physical CDs, if the product is returned as delivered within 14 days).

If you have any questions about delivery or would like to notify us of a return, please get in touch with us here.